"Vicksburg is the key! The war can never be brought to a close until that key is in our pocket... as valuable as New Orleans will be to us, Vicksburg will be more so." ~ Abraham Lincoln

Lincoln knew what he was talking about, and the outcome of the entire Civil War was indeed determined largely by the Union victory at Vicksburg. Vicksburg provided a critical stronghold on one of the United State's most valuable resources - the mighty Mississippi River. Even to this day, the Mississippi provides one of the greatest means of shipping food and goods from the Midwest to the south and then on to global distribution. During the 1860's, in addition to the benefits of transporting goods, the river provided one of the greatest means of transporting troops and weapons. Not only was the river's utility invaluable, but it could be used to divide the southern states, thereby suffocating the Confederacy.

Union General-in-Chief Winfield Scott (the longest active general in the history of the U.S. military, serving at that rank for 47 years) drafted the Anaconda Plan to subdue the seceding states through blockades around the south and control of the Mississippi River, because he knew it's strategic value. There are no other cities along the Mississippi that were so naturally fortified as Vicksburg. Surrounded by swamp land to the north and south, difficult terrain on the Louisiana side of the river, and having the unique geological benefit of 200 foot bluffs that protected it from the naval attacks that enabled then Captain David Glasgow Farragut to take New Orleans, Baton Rouge and Natchez, Vicksburg and Port Hudson became the last vestige for the Confederate forces trying to maintain control of the Mississippi (C.S.A. Maj. Gen. Franklin Gardner surrendered Port Hudson upon hearing of Vicksburg's defeat).

Being such a pivotal city, some of the most respected military leaders of the war squared off against each other at Vicksburg. C.S.A. Lt. Gen John C. Pemberton's forces held the city against the campaign orchestrated by Union Maj. Gen. Ulysses S. Grant. Initially, Grant attempted a direct onslaught of the well entrenched Confederate army on May 19, with a second attempt on May 22. When the direct assaults were deflected, Grant switched tactics and lay siege to the city. After 47 days, on July 4, 1863, Pemberton surrendered. As a result of the defeat on the 4th of July, the city of Vicksburg would not celebrate Independence Day for 80 years.

With over 1350 plaques, tablets, markers, monuments of bronze and stone, 144 mounted cannon, and several significant earthworks, the Vicksburg National Military Park provides plenty of these features to provide interest to everyone from the casual observer to the most well versed Civil War scholar. Even if all these features were absent, the serene, tranquil rolling hills would still make for a beautiful park to drive or walk through, and offer a stark contrast to the violent events that transpired here.

With so many markers in the park, it may seem counter-intuitive to think that the park once intentionally removed and destroyed some of them, but it did exactly that. In 1942, the U.S. found itself engrossed in World War II, and the demand for natural resources was at an all time high. All branches of government, including the National Park Service, were called upon to assist in the war effort. Officials chose approximately 145 of the largest and heaviest cast iron tablets and markers at Vicksburg to melt down for the construction of needed military supplies and equipment.

Park officials hoped that after WWII, funds would be allocated to replace the sacrificed tablets, but due to the increased costs of replacing them, only a few of them were restored. In 2007, the Friends of the Vicksburg National Military Park and Campaign initiated an effort to replace and preserve the monuments at the park, and on October 30, 2008, they were able to provide replacements for 22 of the large tablets.

Vicksburg National Military Park, established February 21, 1899, encompasses 1852.75 acres (including the National Cemetery). Through the heart of the park winds a 16 mile road which features 15 officially designated stops as well as the unofficial stop at the U.S.S. Cairo museum between stops 7 and 8. Of course, there are numerous additional opportunities to stop or pause along the way, and the one-way road is amply wide to accommodate such undesignated stops.

Before starting the drive through the park, it is worth checking out the visitor center, which features a short movie, exhibits on the Vicksburg campaign, including life size dioramas depicting soldier life and the caves that the majority of the citizens of Vicksburg lived in throughout the conflict, and a nice fibre optic map that shows troop movements throughout the campaign. Outside the visitor center are a number of other exhibits worth a look. Directly outside, still under the cover of the structure, sits a 12-lb bronze howitzer. The only cannon at the park out of the 144 that is documented to have been used during the campaign, it was manned by Battery A of the First Illinois Light Artillery at the Old Graveyard Road (Stop 5).

Before starting the drive through the park, it is worth checking out the visitor center, which features a short movie, exhibits on the Vicksburg campaign, including life size dioramas depicting soldier life and the caves that the majority of the citizens of Vicksburg lived in throughout the conflict, and a nice fibre optic map that shows troop movements throughout the campaign. Outside the visitor center are a number of other exhibits worth a look. Directly outside, still under the cover of the structure, sits a 12-lb bronze howitzer. The only cannon at the park out of the 144 that is documented to have been used during the campaign, it was manned by Battery A of the First Illinois Light Artillery at the Old Graveyard Road (Stop 5).Bordering the parking lot is an array of 11 cannon that is impossible to miss. The Civil War occurred at the height of black powder cannon technology, and this display features a variety of artillery that cover the range that were used by both sides in various applications during the campaign. Included is a bronze 24-lb Field Howitzer, 4.2-in Parrott siege rifle, 32-lb Navy siege gun, 32-lb Brooke rifled gun, 10-in Columbiad (Rodman), 10-in siege mortar, 9-in Dahlgren shell gun, 24-lb siege gun, 12-lb bronze field howitzer, 3-in ordnance rifle, and a Brennan 6-lb gun. Though cannon are often thought of merely as implements of destruction, to the soldiers they were much more. C.S.A. artillerist Major Robert Stiles described the significance of cannon: "The gun is the rallying point of the detachment, it's a point of honor, it's the flag, it's the banner. It is that to which men look, by which they stand, with and for which they fight, and for which they fall. As long as the gun is theirs, they are unconquered, victorious; when the gun is lost all is lost."

Memorial Arch

The tour starts by driving under the Memorial Arch. From October 16-19, 1917, the U.S. Congress sponsored the National Memorial Reunion and Peace Jubilee at Vicksburg. With approximately $35,000 that was left over from the money appropriated for the four day gathering of 8000 veterans, a memorial was commissioned. The Memorial Arch, sculpted by Charles Lawhon out of granite from Stone Mountain, GA, was dedicated in 1920 on Clay Street. Considered a traffic hazard, it was relocated to the park entrance in 1967. Since then, it has been a fitting greeting to visitors to Vicksburg, which, being one of the most heavily monumented parks in the world, has been declared the "art park of the world." It is also one of the most accurately mapped military parks, as the Confederate and Union siege lines were marked by veterans of the campaign in the early 1900's.

The tour starts by driving under the Memorial Arch. From October 16-19, 1917, the U.S. Congress sponsored the National Memorial Reunion and Peace Jubilee at Vicksburg. With approximately $35,000 that was left over from the money appropriated for the four day gathering of 8000 veterans, a memorial was commissioned. The Memorial Arch, sculpted by Charles Lawhon out of granite from Stone Mountain, GA, was dedicated in 1920 on Clay Street. Considered a traffic hazard, it was relocated to the park entrance in 1967. Since then, it has been a fitting greeting to visitors to Vicksburg, which, being one of the most heavily monumented parks in the world, has been declared the "art park of the world." It is also one of the most accurately mapped military parks, as the Confederate and Union siege lines were marked by veterans of the campaign in the early 1900's. The first prominent memorial along the route is the Minnesota State Memorial. A granite obelisk standing 90 feet tall, at it's base is a bronze woman named the "Statue of Peace." She holds a laurel wreath while safeguarding a sword and a shield that each of the armies have placed in her care. The memorial, created by William Couper at a cost of $24,000, was dedicated May 24, 1907.

The first prominent memorial along the route is the Minnesota State Memorial. A granite obelisk standing 90 feet tall, at it's base is a bronze woman named the "Statue of Peace." She holds a laurel wreath while safeguarding a sword and a shield that each of the armies have placed in her care. The memorial, created by William Couper at a cost of $24,000, was dedicated May 24, 1907. As a result of the natural border along the west of the city, Pemberton focused the defenses into a crescent around the east side of the city, terminating at the Mississippi River to the north and south. The bulk of Grant's initial 30,000 troops (during the siege, his forces grew to 70,000) were focused along the outside of this crescent, which Pemberton defended with 30,000 men. The road starts out along the Union side of the crescent for tour stops 1-8 and again for stop 15, while stops 9-14 are on the Confederate line.

As a result of the natural border along the west of the city, Pemberton focused the defenses into a crescent around the east side of the city, terminating at the Mississippi River to the north and south. The bulk of Grant's initial 30,000 troops (during the siege, his forces grew to 70,000) were focused along the outside of this crescent, which Pemberton defended with 30,000 men. The road starts out along the Union side of the crescent for tour stops 1-8 and again for stop 15, while stops 9-14 are on the Confederate line.Tour Stop 1

Driving around the corner toward tour stop 1 at Battery DeGolyer, the forested area gives way to the rolling hills of one of the largest battlegrounds in the park. When I drove through, the addition of contrast from the exposed ochre soil added another dimension to the scale and beauty of the area. Of course, barren land is not the normal presentation of the battlefield. When Congress established the park, it set a requirement to restore the "field to its condition at the time of the battle." At the time of the battle, the soldiers had a clear view of the opposing lines, but due to the designation as a National Park, the forest had encroached on the field, concealing some of the earthworks.

In 2005 and 2006, the National Park Service began restoring the park at the Railroad Redoubt, one of the other nine major fortifications in the park. Under the park's Cultural Landscape Plan and Environmental Assessment approved in 2009, as a result of the success of that restoration, the project was expanded to include the areas of Old Jackson Road/Battery DeGolyer/Third Louisiana Redan, Railroad Redoubt/Fort Garrott, and The Graveyard Road near it's intersection with Union Avenue. The intent of the project is to minimize the amount of woodland removed in order to restore the terrain of the most important historic areas to help visitors better understand how it was in 1863.

The Michigan State Memorial demarcates the edge of Battery DeGolyer. It looks much like a miniature version of the Minnesota State Memorial. Dedicated November 10, 1916, it is a 37 foot tall obelisk carved by Herbert Adams. Though it also features a woman at it's base, Adams carved the woman, who represents the Spirit of Michigan, out of marble.

The Michigan State Memorial demarcates the edge of Battery DeGolyer. It looks much like a miniature version of the Minnesota State Memorial. Dedicated November 10, 1916, it is a 37 foot tall obelisk carved by Herbert Adams. Though it also features a woman at it's base, Adams carved the woman, who represents the Spirit of Michigan, out of marble. Union Maj. Gen. James B. McPherson's primary objectives were the Great Redoubt and the Third Louisiana Redan, which guarded the Jackson Road into the city of Vicksburg. The row of cannon pointing across the 600 yard expanse at the Great Redoubt, the highest and one of the best fortified positions on the battlefield. The redoubt, a square, enclosed earthwork that proved virtually impenetrable throughout the siege, is readily identified. Not only is it the highest point on the whole battlefield, at 397 feet above sea level, but also towering over it is the 81 foot tall Doric column of the Louisiana State Memorial. The memorial, dedicated July 10, 1919, features an eternal flame on top and a relief carving of a brown pelican and it's hatchlings, the Louisiana State bird.

Union Maj. Gen. James B. McPherson's primary objectives were the Great Redoubt and the Third Louisiana Redan, which guarded the Jackson Road into the city of Vicksburg. The row of cannon pointing across the 600 yard expanse at the Great Redoubt, the highest and one of the best fortified positions on the battlefield. The redoubt, a square, enclosed earthwork that proved virtually impenetrable throughout the siege, is readily identified. Not only is it the highest point on the whole battlefield, at 397 feet above sea level, but also towering over it is the 81 foot tall Doric column of the Louisiana State Memorial. The memorial, dedicated July 10, 1919, features an eternal flame on top and a relief carving of a brown pelican and it's hatchlings, the Louisiana State bird.On May 19, 1863, Grant ordered a direct assault against the rebel line. Despite their efforts, McPherson's men weren't able to mount a serious threat to the defenses. Two days later, Grant would orchestrate a more concentrated assault, with Maj. Gen. John McClernand on the left, McPherson in the middle, and Maj. Gen. William T. Sherman on the right. During the attack, McPherson's troops charged through the no man's land with 20 foot ladders in attempt to scale the Great Redoubt, but despite their best efforts, they were again repulsed by the Confederate stronghold. After the battle, Union losses exceeded 3,000 men.

As the siege ensued, the Union army set to work digging. 20,000 feet of trenches, called saps, were dug, zig-zagging their way up to Confederate lines. By the time Pemberton surrendered, some of these were within 10 feet prompting one of enemy forces. The troops became so proficient at digging that they could dig a trench with a shovel or spade in one hand and a rifle in the other. With so much digging, one of the Union soldiers recalled, "Every man in the investing line became an Army engineer day and night."

Major General John A. Logan, who served under McPherson, was responsible for constructing the saps that snaked up to the base of the Third Louisiana Redan, known as Logan's Approach. Just past Battery DeGolyer is a statue of Logan.

Tour Stop 2

The Shirley House, which was owned by James and Adeline Shirley, is the second official tour stop. Called the White House by soldiers, it is the only remaining structure from before the war (the other building near the Great Redoubt is the Old Administration Building, which was built in 1937 on plans based on an antebellum house in Natchez, MS). As the Confederates were pushed into Vicksburg by the advancing Union army, the soldiers were instructed to burn all the houses in front of their defenses. The soldier that was assigned to raze the Shirley house was shot, and subsequently died in a crawl space, before he could set the blaze.

Mrs. Shirley, her servants, and her 15 year old son Quincy refused to leave the home, and were subsequently caught in the crossfire as the Union troops advanced on Vicksburg. She displayed a white flag and they huddled by the chimney for three days before a cease-fire was negotiated. During those three days, Shirley recalled, "Bullets came thick and fast, shells hissed and screamed through the air, cannon roared, the dead and dying were brought into the old house." Union soldiers escorted Mrs. Shirley and her son to a ravine near her house, where they lived in a cave for a while during the battle. After the house was vacated by Mrs. Shirley, it served as the headquarters for the staff of the 45th Illinois Infantry.

Mrs. Shirley, her servants, and her 15 year old son Quincy refused to leave the home, and were subsequently caught in the crossfire as the Union troops advanced on Vicksburg. She displayed a white flag and they huddled by the chimney for three days before a cease-fire was negotiated. During those three days, Shirley recalled, "Bullets came thick and fast, shells hissed and screamed through the air, cannon roared, the dead and dying were brought into the old house." Union soldiers escorted Mrs. Shirley and her son to a ravine near her house, where they lived in a cave for a while during the battle. After the house was vacated by Mrs. Shirley, it served as the headquarters for the staff of the 45th Illinois Infantry.When Quincy Shirley evacuated the house, he left behind a coonskin cap. Lt. Henry C. Foster of the 23rd Indiana Infantry picked it up and wore it for the duration of the war. Lieutenant Foster was one of the most accurate sharpshooters in the army, and earned the nickname "Coonskin" Foster. In early June, under the cover of darkness, he built a tower of railroad ties along the Jackson Road, which afforded him a great vantage point to pick off Confederate troops. Grant visited "Coonskin's Tower" several times throughout the siege to evaluate Vicksburg's defenses.

Impossible to miss, the Illinois State Memorial, situated between the Shirley House and the Third Louisiana Redan, is the grandest monument in Vicksburg National Military Park. Modeled after the Pantheon by W. L. B. Jenney and sculpted by Charles J. Mulligan, it stands 62 feet tall. It's base and stairway are constructed of Stone Mountain, GA granite, and Georgia white marble was used for the dome and walls. 47 steps lead to the portico - one for each day of the siege.

Impossible to miss, the Illinois State Memorial, situated between the Shirley House and the Third Louisiana Redan, is the grandest monument in Vicksburg National Military Park. Modeled after the Pantheon by W. L. B. Jenney and sculpted by Charles J. Mulligan, it stands 62 feet tall. It's base and stairway are constructed of Stone Mountain, GA granite, and Georgia white marble was used for the dome and walls. 47 steps lead to the portico - one for each day of the siege. A gilt eagle guards the entrance, and three quotes from prominent Illinois leaders, each of whom were instrumental to the success of not just the Union's Vicksburg campaign, but of the entire war effort, are inscribed above the doorway:

"The mystic chords of memory, stretching from every battlefield, and patriot grave, to every living heart and hearthstone all over this broad land, will yet swell the chorus of the union, when again touched, as surely they will be by the better angels of our nature." ~ Abraham Lincoln

"We have but little to do to preserve peace, happiness and prosperity at home and the respect of other nations. Our experience ought to teach us the necessity of the first, our power secures the latter." ~ Ulysses S. Grant

"God forbid that I should say aught in malice against the south. I look beyond the blue waves of the Ohio and upon the green hills of Kentucky and there is the grave of my mother." Richard Yates (Governor of Illinois during the war)

Inside, 60 bronze plaques record the names of the 36,325 Illinois men who served in the Vicksburg campaign.

The fourth monument erected in the park, the Illinois State Monument was dedicated October 26, 1906, and completed at a cost of $194,423.92 (today's equivalent is nearly $5M), making it the most expensive of all the memorials in the park (the next most expensive, Iowa - $100,000 in 1912, and Alabama - $150,000 in 1951, weren't even half as expensive when adjusted for inflation).

The fourth monument erected in the park, the Illinois State Monument was dedicated October 26, 1906, and completed at a cost of $194,423.92 (today's equivalent is nearly $5M), making it the most expensive of all the memorials in the park (the next most expensive, Iowa - $100,000 in 1912, and Alabama - $150,000 in 1951, weren't even half as expensive when adjusted for inflation).

The Illinois State Commission specified that no device of war could appear on the memorial, making it one of the few in the park to be void of such ornamentation, yet it wants for none, and is spectacular to behold outside and in. To emphasize tne sentiment of peace and unity, the phrase "With malice toward none" is engraved into the outside of the memorial.

The Third Louisiana Redan was constructed to support the Great Redoubt in defending the Jackson Road into Vicksburg. Similar to a redoubt, the redan is a triangular shaped fort with it's tip pointed toward the enemy. This is the only fort under which a mine was successfully exploded.

To avoid further undue risk to his troops in direct assault, Grant planned to ignite mines under rebel fortifications to provide an opening for his soldiers to rush the stunned Confederate soldiers. At the base of the Third Louisiana Redan is a statue of Capt. Andrew Hickenlooper. Hickenlooper was tasked with utilizing Logan's Approach to dig a mine under the redan. Though the Third Louisiana Infantry knew the mine was being dug, their attempts to deter Hickenlooper with counter mines, grenades, and sharpshooters failed.

To avoid further undue risk to his troops in direct assault, Grant planned to ignite mines under rebel fortifications to provide an opening for his soldiers to rush the stunned Confederate soldiers. At the base of the Third Louisiana Redan is a statue of Capt. Andrew Hickenlooper. Hickenlooper was tasked with utilizing Logan's Approach to dig a mine under the redan. Though the Third Louisiana Infantry knew the mine was being dug, their attempts to deter Hickenlooper with counter mines, grenades, and sharpshooters failed.During the course of the siege, Union soldiers improvised three cannon by banding felled, hollowed tree trunks with iron. These were able to fire 6 or 12 pound projectiles. On July 1, a second mine was successfully ignited under the redan, which caused substantial damage, but wasn't followed by an infantry assault. When the second mine went off, a black man who was digging a counter mine was propelled into the air. When asked how high he went, he replied, "Dunno, massa, but tink about tree mile."

Tour Stop 4

Continuing back down the winding main road, the fourth official tour stop, Ransom's Gun Path, appears around a bend. It is possibly the easiest tour stop to miss along the route. Directly ahead is the first glimpse of the upcoming Wisconsin Monument, and Ransom's Gun path is rather unremarkable looking - not much more than a grassy corridor through the wood. A simple bronze placard sits by the road to mark the location. Here, Brig. Gen. Thomas E.G. Ransom needed additional artillery support, but the hilly terrain made it difficult to move cannon into the position needed. Some of his infantrymen helped the 2nd Illinois Light Artillery dismantle two 12 pounders and drag them over the hills to an earthwork about 100 yards from the rebel trenches, where they were reassembled, and resumed their bombardment.

Private Albert D.J. Cashier, of the 95th Illinois Infantry, was stationed near here during the siege. Cashier served in the Army for 3 years, but it was not until about 50 years after the war that Cashier was injured by accident and rushed to a hospital, when it was discovered Cashier was a woman. Jennie Hodges had disguised herself as Albert Cashier in 1862 to fight for the Union.

Not realizing that there was a turnout for the Wisconsin State Memorial around the next corner, I left my car at the turnout for Ransom's path, and walked up the road to it. A bronze cavalryman and an infantryman flank the 122 foot column of the Wisconsin State Memorial, dedicated May 22, 1911. At the base of the column is a relief tablet of a Union and Confederate soldier shaking hands in friendship.

Not realizing that there was a turnout for the Wisconsin State Memorial around the next corner, I left my car at the turnout for Ransom's path, and walked up the road to it. A bronze cavalryman and an infantryman flank the 122 foot column of the Wisconsin State Memorial, dedicated May 22, 1911. At the base of the column is a relief tablet of a Union and Confederate soldier shaking hands in friendship.

The Wisconsin State Memorial is topped with a six foot bronze sculpture of a war eagle. Not just any eagle, this one's name is "Old Abe," who served as the living mascot of Company C, 8th Wisconsin Infantry. The bald eagle, which was once wounded in battle, achieved so much notoriety during the war that P.T. Barnum attempted to add it to his circus, but the state of Wisconsin rejected his offer to buy it. Old Abe continues to be honored to this day as the symbol of the symbol of the U.S. Army's 101st Airborne, known as the "Screaming Eagles."

The Wisconsin State Memorial is topped with a six foot bronze sculpture of a war eagle. Not just any eagle, this one's name is "Old Abe," who served as the living mascot of Company C, 8th Wisconsin Infantry. The bald eagle, which was once wounded in battle, achieved so much notoriety during the war that P.T. Barnum attempted to add it to his circus, but the state of Wisconsin rejected his offer to buy it. Old Abe continues to be honored to this day as the symbol of the symbol of the U.S. Army's 101st Airborne, known as the "Screaming Eagles."

Old Abe wasn't the only living mascot in the war, nor was a bald eagle the most unusual. The 43d Mississippi Infantry's mascot, Douglas the Camel, remained with the regiment until Vicksburg where he was killed by Union sharpshooters. Douglas is honored with his own grave marker in Vicksburg's Cedar Hill Cemetery. I didn't make it to that cemetery to find the marker, which features an image of him and a colored Confederate flag. The marker reads, "'Old Douglas' was the 'faithful, patient' camel of the 43rd MS Infantry Vols, C.S.A. Douglas was a dromedary camel, and was given to Col. W.H. Moore by Lt. W.H. Hargrove of Co. B. Moore assigned Douglas to the band. Douglas at first frightened all the 43rd's horses, but soon became a favorite of both beasts and men. The 43rd was henceforth called 'The Camel Regiment.' Douglas served in the Iuka, Corinth, Central MS Rail Road, and Vicksburg Campaigns. Intentionally killed by yankee sharpshooters near the end of the siege, he may have been eaten by the starving Confederates. Douglas' death was greatly mourned, and as a 43rd vet wrote about him, 'His service merits record.'"

On May 25, this area between the Third Louisiana Redan and the Stockade Redan was the site of a rather unusual sight. A two and a half hour truce was negotiated to care for the dead and wounded covering the field. Men from each side were free to talk to each other, swapping interesting stories and trading extensively with their enemies.

Tour Stop 5

The attack on Stockade Redan was overseen by General Sherman, who directed the 55th Illinois Infantry under Gen. Francis P. Blair Jr. to attack the redan. The Stockade Redan guarded the Graveyard Road, and was Sherman's primary objective. The Confederates had obstructed the already rough terrain with felled trees, making it difficult for Blair's three brigades to advance.

During the initial assault the Union forces were running low on ammunition. Colonel Malmborg asked for volunteers to run for a replenished supply. Orion P. Howe, a drummer boy for the 55th volunteered for the dangerous duty. While running down the Graveyard Road, Howe was seriously injured from a shot in the leg. In spite of his injuries, he continued to the rear to notify General Sherman of the situation. For his bravery, he was later awarded the Medal of Honor, and, being 14 years old at the time, he remains the youngest recipient of the nation's highest military honor.

During the initial assault the Union forces were running low on ammunition. Colonel Malmborg asked for volunteers to run for a replenished supply. Orion P. Howe, a drummer boy for the 55th volunteered for the dangerous duty. While running down the Graveyard Road, Howe was seriously injured from a shot in the leg. In spite of his injuries, he continued to the rear to notify General Sherman of the situation. For his bravery, he was later awarded the Medal of Honor, and, being 14 years old at the time, he remains the youngest recipient of the nation's highest military honor.In the second attack, Grant ordered his forces to advance directly along the Graveyard Road to avoid the more difficult terrain and obstructions. 150 volunteers carried planks and ladders to bridge the ditch in front of the redan. Though they had some success in getting to the exterior slope, the intense fire from the it's defenders forced a retreat. Though the two direct offensives to the redan were repulsed, resulting in heavy casualties for Sherman's troops, Grant reasoned that had he not attempted a conventional attack, his troops wouldn't have been able to diligently devote themselves to the siege.

The section of road from tour stop 5 to tour stop 6 constitutes the heaviest concentration of monuments in this already heavily monumented park.

Ohio is unique among the states in that instead of honoring it's soldiers with a singular monument, it chose to honor each of it's 39 units with their own memorial. Bullet shaped memorials, like the one nearby honoring the 53rd Ohio Infantry commanded by Col. Wells S. Jones, were used for infantry corps, while a tripod of cannon, one of which is near the next official stop, were used for artillery units.

Ohio is unique among the states in that instead of honoring it's soldiers with a singular monument, it chose to honor each of it's 39 units with their own memorial. Bullet shaped memorials, like the one nearby honoring the 53rd Ohio Infantry commanded by Col. Wells S. Jones, were used for infantry corps, while a tripod of cannon, one of which is near the next official stop, were used for artillery units.

African American soldiers were involved in the armies and navies of both the Union and the Confederacy during the Civil War. Over 178,000 served in the Union army and nearly 18,000 served in the Union navy. It is unknown how many black soldiers served the Confederacy. Dedicated February 14, 2004, the African American Monument is the first monument on any Civil War battlefield administered by the NPS to honor the contributions of black soldiers. Proposed by Vicksburg Mayor Robert M. Walker, the City of Vicksburg contributed $25,000 and the State of Mississippi added $250,000 toward the project.

African American soldiers were involved in the armies and navies of both the Union and the Confederacy during the Civil War. Over 178,000 served in the Union army and nearly 18,000 served in the Union navy. It is unknown how many black soldiers served the Confederacy. Dedicated February 14, 2004, the African American Monument is the first monument on any Civil War battlefield administered by the NPS to honor the contributions of black soldiers. Proposed by Vicksburg Mayor Robert M. Walker, the City of Vicksburg contributed $25,000 and the State of Mississippi added $250,000 toward the project.The base is black granite imported from Africa. Mounted atop is the nine foot tall bronze sculpture designed by Dr. J. Kim Sessums of Brookhaven, MS, depicting three black men. Two of the men are soldiers of the 1st and 3rd Mississippi Infantry, Black Descent, who participated in the Vicksburg campaign. The third is a civilian. The civilian looks to the past, and the institution of slavery that was left behind, while one soldier looks to the future freedom that he helped to secure. Being held up by them, the wounded soldier in the middle represents the sacrifice of blood that was paid for that freedom.

The most contemporary style monument on the battlefield is the Kansas State Memorial. The memorial, erected in 1960, is an abstract representation of the stages of the country's history. A plaque placed by the Daughters of Union Veterans of the Civil War explains the symbolism: "The bottom circle represents the unity of the pre-Civil War era. The broken circle in the center represents the Union torn asunder by the war 1861-1865. The perfect circle at the top depicts the regained unity of the post war era. An eagle atop typifies the glorious majesty of our country."

The Rhode Island State Memorial honors the 7th Rhode Island Infantry led by Col. Zenas R. Bliss. Dedicated on November 11, 1908, the bronze statue sculpted by Frank Edwin Elwell depicts an infantryman carrying a tattered flag into battle.

The Rhode Island State Memorial honors the 7th Rhode Island Infantry led by Col. Zenas R. Bliss. Dedicated on November 11, 1908, the bronze statue sculpted by Frank Edwin Elwell depicts an infantryman carrying a tattered flag into battle.General Grant's Headquarters

Ulysses S. Grant originally occupied a wood frame house on a grassy knoll behind the Union line as his headquarters. During the night of May 21, he was awoken by soldiers, who, unaware he was inside, were pulling boards off the house to construct ladders and planks for the next day's assault on the Stockade Redan. After the initial shock and being informed of the purpose of the destruction of his quarters, he approved it's demolition. Grant spent the duration of the siege quartered in a tent in this circle.

Dedicated on October 17, 1917 during the National Memorial Reunion and Peace Jubilee, the 43 foot tall obelisk of the New York State Memorial sits at the entrance to Grant's Headquarters circle. Presenting it at the ceremony was Col. Andrew D. Baird, a veteran of the 79th New York Infantry Regiment, which served under Sherman during the Civil War, but arrived in Mississippi too late to serve in the siege of Vicksburg.

Dedicated on October 17, 1917 during the National Memorial Reunion and Peace Jubilee, the 43 foot tall obelisk of the New York State Memorial sits at the entrance to Grant's Headquarters circle. Presenting it at the ceremony was Col. Andrew D. Baird, a veteran of the 79th New York Infantry Regiment, which served under Sherman during the Civil War, but arrived in Mississippi too late to serve in the siege of Vicksburg. On November 14, 1903, Massachusetts became the first state to erect a memorial to its soldiers who served during the Vicksburg campaign on the grounds of Vicksburg National Military Park. The Massachusetts State Memorial honors the three regiments from that state that served in the siege, and features a bronze infantryman sculpted by Theo Alice Ruggles Kitson, mounted on a 15 ton boulder from Massachusetts.

On November 14, 1903, Massachusetts became the first state to erect a memorial to its soldiers who served during the Vicksburg campaign on the grounds of Vicksburg National Military Park. The Massachusetts State Memorial honors the three regiments from that state that served in the siege, and features a bronze infantryman sculpted by Theo Alice Ruggles Kitson, mounted on a 15 ton boulder from Massachusetts.The New Hampshire State Memorial is the second oldest monument in the park. An orb topped 20 foot tall column of rough hewn granite, it was erected in November 1904. The top of it can be seen in the background of the picture of the Massachusetts State Memorial.

The Pennsylvania State Memorial, dedicated March 24, 1906, is a granite wall mounted on an oval pedestal. It features five bronze heads that portray each of the Pennsylvania unit commanders.

An equestrian statue of General Grant is mounted on the knoll, approximately where the wooden house originally stood. The statue, cast in bronze, was sculpted by Frederick C. Hibbard in 1918 and unveiled in 1919. Hibbard commented on the construction of Grant's statue, saying, "I was commissioned by the State of Illinois to make the General U. S. Grant equestrian statue for the Vicksburg National Park, Mississippi. The only requirements of the State Commissioners were that General Grant be mounted upon a quiet, gentle, horse, and be depicted as he was during the Siege of Vicksburg. I could not fulfill the latter requirement because the General wore a blouse and his pants were over his boots, Had he been made in sculpture during the siege, he would have looked like a rooster with its tail feathers pulled out and spurs cut off."

An equestrian statue of General Grant is mounted on the knoll, approximately where the wooden house originally stood. The statue, cast in bronze, was sculpted by Frederick C. Hibbard in 1918 and unveiled in 1919. Hibbard commented on the construction of Grant's statue, saying, "I was commissioned by the State of Illinois to make the General U. S. Grant equestrian statue for the Vicksburg National Park, Mississippi. The only requirements of the State Commissioners were that General Grant be mounted upon a quiet, gentle, horse, and be depicted as he was during the Siege of Vicksburg. I could not fulfill the latter requirement because the General wore a blouse and his pants were over his boots, Had he been made in sculpture during the siege, he would have looked like a rooster with its tail feathers pulled out and spurs cut off."Tour Stop 6

At what is now known as Thayer's Approach, Brig. Gen. John M. Thayer was tasked with taking a ridge occupied by the 26th Louisiana Stockade. During the attacks on May 19 and May 22, Thayer's troops managed to advance up the hill to where the blue markers now stand, but were repulsed by the 26th Louisiana, which was assisted on the right by the 31st Louisiana. One of the best places in the park to fully grasp the effectiveness of the saps, on May 30, Thayer set his men to work digging a trench up the hill to protect his soldiers from rebel snipers.

At what is now known as Thayer's Approach, Brig. Gen. John M. Thayer was tasked with taking a ridge occupied by the 26th Louisiana Stockade. During the attacks on May 19 and May 22, Thayer's troops managed to advance up the hill to where the blue markers now stand, but were repulsed by the 26th Louisiana, which was assisted on the right by the 31st Louisiana. One of the best places in the park to fully grasp the effectiveness of the saps, on May 30, Thayer set his men to work digging a trench up the hill to protect his soldiers from rebel snipers. The sap was started on the other side of the parapet, and a tunnel was bore through it to allow soldiers to enter the trench under the protection of cover. The tunnel, which is preserved by bricks, still passes under the road, and can be accessed by a stairway leading down to it from the opposite side of the road. In order to protect the men digging the sap from Confederate bullets, bundles of cane, called sap rollers, were laid across the top of the trench. By the time of the surrender, Thayer's men had nearly finished digging a mine shaft, like the ones used at the Third Louisiana Redan, to undermine the rebel's defenses.

The sap was started on the other side of the parapet, and a tunnel was bore through it to allow soldiers to enter the trench under the protection of cover. The tunnel, which is preserved by bricks, still passes under the road, and can be accessed by a stairway leading down to it from the opposite side of the road. In order to protect the men digging the sap from Confederate bullets, bundles of cane, called sap rollers, were laid across the top of the trench. By the time of the surrender, Thayer's men had nearly finished digging a mine shaft, like the ones used at the Third Louisiana Redan, to undermine the rebel's defenses.

In response to the sap construction, on June 9 the 26th Louisiana started building a rough stockade on the Confederate front, which they completed the night of June 11. They added a trench immediately behind the stockade on June 15. A counter mine against the Union approach was dug from the trench, but was never fired.

The Navy Memorial is the tallest monument on the battlefield. The 202 foot tall obelisk pays tribute to the contributions of the Union navy operations in the Vicksburg campaign. Around the it's base are statues of the 4 fleet commanders - Admirals David Glasgow Farragut and David Dixon Porter, who were foster brothers that became the first two men to attain the rank of Admiral in the US Navy, and Flag Officers Charles Henry Davis and Andrew Hull Foote.

The Navy Memorial is the tallest monument on the battlefield. The 202 foot tall obelisk pays tribute to the contributions of the Union navy operations in the Vicksburg campaign. Around the it's base are statues of the 4 fleet commanders - Admirals David Glasgow Farragut and David Dixon Porter, who were foster brothers that became the first two men to attain the rank of Admiral in the US Navy, and Flag Officers Charles Henry Davis and Andrew Hull Foote. The Vicksburg campaign couldn't have been planned or conducted as it was without the assistance of the Navy. The Mississippi squadron consisted of about 26 gunboats and light draughts that were instrumental to the Union's success. On April 16, Admiral Porter, who commanded naval operations on inland waters, was steaming his way downstream toward Vicksburg when his ships were discovered by the Confederates guarding the Mississippi River.

The Vicksburg campaign couldn't have been planned or conducted as it was without the assistance of the Navy. The Mississippi squadron consisted of about 26 gunboats and light draughts that were instrumental to the Union's success. On April 16, Admiral Porter, who commanded naval operations on inland waters, was steaming his way downstream toward Vicksburg when his ships were discovered by the Confederates guarding the Mississippi River.To illuminate the gunships, the Rebels set fire to tar barrels along the river bank and houses in the town of De Soto, which was on the Louisiana shore. Although each of the 8 ships was hit along the 4 mile stretch of Vicksburg river front, only one was sunk. Porter then ferried 6 of Grant's divisions across the river to Bruinsburg, MS. Afterward, he positioned his ships behind the protection of the De Soto Peninsula and used his 17,000lb mortars to launch 100lb shells into the city, which they did so frequently that the only relief for the Confederate batteries came during the three meal times for the naval gunners.

Tour Stop 7

Battery Selfridge is named after it's commander, who was not a typical Army battery commander. On December 12, 1862, the ironclad U.S.S. Cairo was part of a 5 boat search and destroy flotilla was moving up the Yazoo River. The Cairo had only been in service for 11 months when it became the first ship in history to be sunk by an electronically detonated mine. After it sank, its commander, Lieutenant Commander Thomas o. Selfridge, Jr., was reassigned to the Conestoga, then volunteered to command the only land based battery that was not only fully outfitted with naval guns, but also was manned entirely by Union sailors.

Battery Selfridge is named after it's commander, who was not a typical Army battery commander. On December 12, 1862, the ironclad U.S.S. Cairo was part of a 5 boat search and destroy flotilla was moving up the Yazoo River. The Cairo had only been in service for 11 months when it became the first ship in history to be sunk by an electronically detonated mine. After it sank, its commander, Lieutenant Commander Thomas o. Selfridge, Jr., was reassigned to the Conestoga, then volunteered to command the only land based battery that was not only fully outfitted with naval guns, but also was manned entirely by Union sailors.Driving down the hill toward the National Cemetery, a large white semi-permanent tent comes into view. As I approached it, I realized what was underneath the tent, and I was practically dumbstruck.

The HMS Warrior, a restored British super frigate, is berthed in Portsmouth; also British built, the Huáscar, which was built for Peru and seized by Chili, is berthed at the port of Talcahuano; the HNLMS Schorpioen, a French built vessel, and the HNLMS Buffel, of Scottish construction, are both surviving Netherlands Navy ram ships. All four of these are primarily traditionally constructed wooden frigates. The U.S. built ironclads of the time took the armouring to a whole other level, but due to their active war use, only the casemate of the C.S.S. Jackson at Port Columbus, GA; the wooden hull of the C.S.S. Neuse at Kinston, NC; some parts of the U.S.S. Monitor at Newport News, VA; and to my surprise, the U.S.S. Cairo is on display under the tent at Vicksburg. While reproductions of the U.S.S. Monitor and the C.S.S. Neuse exist, the Cairo is the most completely preserved of the U.S. ironclads.

James B. Eads, named after his mother's cousin, then Congressman and subsequently the 15th U.S. President, James Buchanan, was a wealthy industrialist, civil engineer, and inventor who initially made his fortune in salvage, retrieving the remains of sunken ships and their cargo from the bottom of the Mississippi River. At the onset of the Civil War, Eads owned several shipyards along the Mississippi River, and was contracted by the Union to build their needed warships. By the end of the war, he built more than 30 river ironclads of various designs. It was at Ead's suggestion that the City class design featured a catamaran style hull, as it provided multiple sealed chambers that would allow a ship to absorb more battle damage without sinking than other hull designs. Eads collaborated with Navy Commander John Rodgers, combining Rodger's military experience and Eads' river engineering knowledge to develop the specifications for the needed ironclad gunships. It was through this collaboration that they determined, among other requirements, that the ships should be armoured well enough to withstand a direct hit from the artillery of the day, resulting in the iron cladding.

The U.S.S. Cairo was commissioned in January of 1862 as the first of seven ironclad ships made for the Union based on the City class (so named because these seven were named after seven cities along the Mississippi River or it's tributaries), which were designed by Samuel M. Pook, a naval architect who was based in Cairo, Illinois. In order to provide a shallow draught of only 6 feet while displacing 512 tons and maintain maneuverability along inland river waters, Pook designed them to be relatively broad (beam of 51'2"), with a short length of 175', resulting a small length to beam ratio of 3.4, earning the City class gunboats the nickname of Pook Turtles. Pook also incorporated a triple catamaran style hull, based on the specifications set by Rodgers and Eads, which was well suited to the stout design.

In nautical terminology, hogging is the tendency of a ship's ends to droop, and it's center to rise up like a hog's back. This tendency is intensified when a boat is very long in proportion to it's depth, and especially under the stress of heavy loads. Without the deep beam of a seagoing vessel to add structural rigidity, another method of evenly distributing loading was needed to ensure the iron clads were sound. 1" to 2-1/2" thick iron rods called hog chains were attached to the hull, fore and aft, and routed over braces in the middle of each side to prevent hogging. The starboard hog chains have been restored on the Cairo.

The gunboat's capstan was capable of moving weights of several tons. It was a winch which could be operated by steam from the boilers or hand driven used for pulling in the anchor, moving guns around the gun deck, and hauling lines.

The gunboat's capstan was capable of moving weights of several tons. It was a winch which could be operated by steam from the boilers or hand driven used for pulling in the anchor, moving guns around the gun deck, and hauling lines. The City class ironclads were propelled by a 22 foot recessed paddle wheel, which sat protected by the side casemates, in a 28' x 18' deck opening. The paddle wheel, constructed of 5 iron spiders and uniform width wood buckets, was driven by a steam engine mounted on each side of it's axle operating 90* apart. In each engine, designed by Thomas Merritt, five fire tube boilers 36" in diameter and 24' long fed a 22" piston that drove a Pitman Arm with a 6 foot stroke. The boilers operated at 140 pounds per square inch steam pressure and consumed almost a ton of coal per hour. Cairo's boilers are among the oldest and best surviving examples of the type.

The City class ironclads were propelled by a 22 foot recessed paddle wheel, which sat protected by the side casemates, in a 28' x 18' deck opening. The paddle wheel, constructed of 5 iron spiders and uniform width wood buckets, was driven by a steam engine mounted on each side of it's axle operating 90* apart. In each engine, designed by Thomas Merritt, five fire tube boilers 36" in diameter and 24' long fed a 22" piston that drove a Pitman Arm with a 6 foot stroke. The boilers operated at 140 pounds per square inch steam pressure and consumed almost a ton of coal per hour. Cairo's boilers are among the oldest and best surviving examples of the type. Steering was accomplished by way of dual rudders. These were secured by long iron pins called gudgeons, which allowed them to be quickly replaced if damaged during battle. The rudders were operated by cables to the pilot house, which, if hit during battle, could disable steering, rendering the vessel a sitting duck.

Combining the heat of the boilers, the southern summers, and the artillery, the gun deck could be oppressively hot. Skylights were incorporated into the design to provide light and much needed ventilation - allowing fresh air to flow through the gun ports and evacuate hot and smoky air out the top. The picture is of the pilot house, which was another primary surce of ventilation for the ship.

Combining the heat of the boilers, the southern summers, and the artillery, the gun deck could be oppressively hot. Skylights were incorporated into the design to provide light and much needed ventilation - allowing fresh air to flow through the gun ports and evacuate hot and smoky air out the top. The picture is of the pilot house, which was another primary surce of ventilation for the ship. In order to ensure that they posed a serious threat to the enemy, the gunships were fitted with 13 cannon - 3 gunports faced forward, 4 on each side, and 2 to the rear. Though some of the cannon would be upgraded as it became available, in particular the 42 pounder rifles, which were modified smooth bore cannon, rather than purpose built rifles, making them more prone to failure than other gun, the original armament consisted of 3 modern 8 inch Dahlgren smoothbores, 6 rifled 42-pounders, and 6 rifled 32-pounders. A 12 pounder boat howitzer was often added to the armament for use in the event of an attempted boarding.

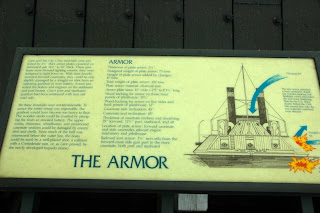

In order to ensure that they posed a serious threat to the enemy, the gunships were fitted with 13 cannon - 3 gunports faced forward, 4 on each side, and 2 to the rear. Though some of the cannon would be upgraded as it became available, in particular the 42 pounder rifles, which were modified smooth bore cannon, rather than purpose built rifles, making them more prone to failure than other gun, the original armament consisted of 3 modern 8 inch Dahlgren smoothbores, 6 rifled 42-pounders, and 6 rifled 32-pounders. A 12 pounder boat howitzer was often added to the armament for use in the event of an attempted boarding. The iron plating was mounted as part of the sloping casemate that enclosed the gun deck. The 2-1/2 inch thick charcoal plate iron was backed by laminated white oak timbers and sheathing varying in thickness from 12-1/2" to 25" thick. Experiments just before the war indicated that it was this combination of the hard, yet brittle iron and the flexibility and strength of oak that made for the best armour of the day. The ships were designed primarily for frontal assault, relying heavily on the most powerful guns equipped, the 3 Dahlgren cannon mounted in the forward gun ports, for the bulk of their offense. The wooden walls here were 19-1/2" thick behind the 13"x2'5"-8'1-1/2" long iron plates, which, combined with the fully armoured bows made the ironclads virtually impenetrable from the front. Their armour continued along the sides, protecting their flanks with 12-1/2" wood backed plating in key areas to protect the boilers and engines. 3-1/2" thick railroad ties covered the stems and sterns and the area from the front casemate to the forward most gun port on each side. Originally, plans called for 75 tons of plate armour, but was expanded by 47 tons to 122 tons of iron.

The iron plating was mounted as part of the sloping casemate that enclosed the gun deck. The 2-1/2 inch thick charcoal plate iron was backed by laminated white oak timbers and sheathing varying in thickness from 12-1/2" to 25" thick. Experiments just before the war indicated that it was this combination of the hard, yet brittle iron and the flexibility and strength of oak that made for the best armour of the day. The ships were designed primarily for frontal assault, relying heavily on the most powerful guns equipped, the 3 Dahlgren cannon mounted in the forward gun ports, for the bulk of their offense. The wooden walls here were 19-1/2" thick behind the 13"x2'5"-8'1-1/2" long iron plates, which, combined with the fully armoured bows made the ironclads virtually impenetrable from the front. Their armour continued along the sides, protecting their flanks with 12-1/2" wood backed plating in key areas to protect the boilers and engines. 3-1/2" thick railroad ties covered the stems and sterns and the area from the front casemate to the forward most gun port on each side. Originally, plans called for 75 tons of plate armour, but was expanded by 47 tons to 122 tons of iron.The armour wasn't the only protection for the gunships. Geometry was a primary concern in their design. Most of the surfaces were at 45* angles, including the whole pilot house, casemates, and the undercut chamfer under the waterline. As a result of these angles and the armour, most shots would simply deflect off the surface, scarcely leaving a trace of the impact.

The resiliency of this combination of angles and armour was tested in the Battle of Hampton Roads. The U.S.S. Merrimack (sometimes mistakenly called the Merrimac as the result of a historian's confusion, which is a different vessel entirely), was set ablaze and sunk by the Union in attempt to keep it from Confederate hands. After salvaging the wreck, the lower hull and machinery became the base of the Confederate's first steam powered ironclad, the C.S.S. Virginia. The Virginia had already destroyed the U.S.S. Cumberland, the U.S.S. Congress, and disabled the U.S.S. Minnesota when the U.S.S. Monitor, the first of the Union ironclads (pre-City class), arrived. The two ironclads shelled each other heavily for about four hours, often at nearly point blank range, with no serious damage to either craft. The world's first engagement of two ironclads demonstrated the benefits of the iron-on-oak construction for withstanding the weaponry of the day.

The resiliency of this combination of angles and armour was tested in the Battle of Hampton Roads. The U.S.S. Merrimack (sometimes mistakenly called the Merrimac as the result of a historian's confusion, which is a different vessel entirely), was set ablaze and sunk by the Union in attempt to keep it from Confederate hands. After salvaging the wreck, the lower hull and machinery became the base of the Confederate's first steam powered ironclad, the C.S.S. Virginia. The Virginia had already destroyed the U.S.S. Cumberland, the U.S.S. Congress, and disabled the U.S.S. Minnesota when the U.S.S. Monitor, the first of the Union ironclads (pre-City class), arrived. The two ironclads shelled each other heavily for about four hours, often at nearly point blank range, with no serious damage to either craft. The world's first engagement of two ironclads demonstrated the benefits of the iron-on-oak construction for withstanding the weaponry of the day.

The remains of the Cairo were lifted from the river, placed on barges and towed to Ingalls Shipyard located on the gulf coast in Pascagoula, Mississippi. There, it was partially restored, and remained in storage. In 1972, the U.S. Congress approved transfer to the NPS and authorized it's restoration, though funding issues prevented any further progress until June 1977. The gunboat restoration project was completed in 1984, and the exhibit opened to the public in 1985. The museum, which opened in November 1980, features showcases the artifacts recovered from the Cairo excavation, including one of the original gun carriages with a fiberglass reproduction gun (the original cannon are displayed on the boat, but the original carriages weren't weathering well under the tent, so they were replaced with reproductions).

The remains of the Cairo were lifted from the river, placed on barges and towed to Ingalls Shipyard located on the gulf coast in Pascagoula, Mississippi. There, it was partially restored, and remained in storage. In 1972, the U.S. Congress approved transfer to the NPS and authorized it's restoration, though funding issues prevented any further progress until June 1977. The gunboat restoration project was completed in 1984, and the exhibit opened to the public in 1985. The museum, which opened in November 1980, features showcases the artifacts recovered from the Cairo excavation, including one of the original gun carriages with a fiberglass reproduction gun (the original cannon are displayed on the boat, but the original carriages weren't weathering well under the tent, so they were replaced with reproductions).Tour Stop 8

The Vicksburg campaign involved over 100,000 Union and Confederate soldiers. By the end, it claimed the lives of 1,413 Rebels and 1,581 Yankees. Another 3,800 Confederates and 1,007 Union soldiers were missing, and 3,878 southerners and 7,554 northerners were wounded, claiming 9,091 Confederate casualties and 10,142 from the Union. With 20,033 casualties in Vicksburg and many more from other battles in the region, 212,938 combat deaths from the whole war, with approximately 625,000 total dead from the war efforts, there was a desperate need for a logistical procedure for dealing with the casualties of the war, since nothing of that level had been seen before or since in this country.

During the course of the war, the dead would generally be buried near where they fell. If they were known, their shallow grave often would be marked, typically with little more than their name scratched into a wooden board. Shallow graves were not a fitting final resting place, so to properly honor the soldiers, a more permanent solution was required.

On April 3, 1862, the first effort of the U.S. government to address this issue came in the form of the War Department's General Order No. 33, which stated, "In order to secure, as far as possible, the decent interment of those who have fallen, or may fall, in battle, it is made the duty of commanding generals to lay off lots of ground in some suitable spot near every battle-field, so soon as it may be in their power and to cause the remains of those killed to be interred, with headboards to the graves bearing numbers, and where practicable, the names of the persons buried in them. A register of each burial ground will be preserved, in which will be noted the marks corresponding with headboards."

This order was substantiated when, on July 17 of the same year, the President was given the authority to purchase cemetery grounds and to securely enclose them to be used for the internment of soldiers who die in service to the country. By the end of the war, 14 national cemeteries had been established. Several subsequent acts and orders followed, but it was not until the Feb. 22, 1867 Act of Congress to provide $750,000 for the funding of the procurement of the land needed and building walls/fences and support buildings that national cemeteries were formally established.

In 1865, the number of Union soldiers buried in national cemeteries surpassed 100,000, and, for the first time, the long term economic viability of wooden headboards was evaluated. Estimating that there would be more than 300,000 soldiers interned at the national cemeteries, with an average cost of $1.23 per headboard, and a life expectancy of less than five years, the original and replacement costs of the markers would be in excess of $1 million. It was decided that a more permanent marker would be more economical and would appease public sentiment that was also leaning toward a more permanent option. Options of stone and zinc coated galvanized iron were considered.

In 1873, the Secretary of War decided the permanent grave markers would be a slab of polished granite or durable stone four inches thick, 10 inches wide, and standing 12 inches above the ground with a curved top, resembling the wooden headboards. On the face, the plot number, rank, name, and state of service of the interred was engraved. This form of headstone, which, in slightly larger dimensions known as the "General" type remains the standard for national cemeteries, became known as the "Civil War" type. For the unidentified dead, a stone marker 6 inches square by 30 inches long was used. The 4 inches of the sides that were above ground and the top were polished, and the grave number was the only marking. These such markers were not only used for the Civil War deceased, but also for replacements of the wooden headboards for soldiers of the Revolutionary War, War of 1812, Mexican War, and the Indian Campaigns.

The Vicksburg National Cemetery is the final resting place for over 17,000 Union soldiers, making it the largest internment of Civil War casualties in the nation. The cemetery encompasses 116.28 acres which was the extreme right flank of the Union siege line, commanded by Gen. Sherman during the campaign. After the war, approximately 300,000 Union soldiers were exhumed throughout the battlefields in the southern states in accordance with the creation of the national cemeteries. As such, the graves are not occupied solely of veterans of the Vicksburg campaign, but include many others who died on battlefields and in hospitals throughout the region. During the war, there wasn't a lot of emphasis on documenting the dead, and dog tags wouldn't be used until the 1900s, so whatever makeshift markings that were arranged for the known dead during the war were sometimes lost before the process of reinterring their remains.

When touring the Vicksburg National Cemetery, only 25% of the headstones are of the Civil War type. With 12,954 unidentified internments of the 18,244 burials, most of the graves are are designated with the small rectangular markers bearing only the grave site number. Compared to 75% buried here, nationally, 54% of the reinterred soldiers from the Civil War are classified as unknown (the highest, at Salisbury National Cemetery in North Carolina, is 99%).

Approximately 1300 of the identified graves at Vicksburg are occupied by veterans from subsequent service and for former caretakers and their families. The cemetery remained open for burial to eligible veterans until May 1961, when it was closed for new occupants except those who had reserved a plot there prior to that date.

The initial establishment of the national cemeteries allowed only for soldiers who died in service to the country during the Civil War to be buried within them. This precluded those that served as Confederates, as the southern states they fought for had seceded, and therefore weren't serving the Union. A revision later would allow anyone who served the country in subsequent service to also be given a plot in a national cemetery, which would allow a former Confederate an internment, but only if they served the U.S. military later.

According to the National Park service, there are at least three known Confederates buried in Vicksburg National Cemetery, two of whom have graves designated by Confederate headstones. In the late 1860s, Private Rueben White of the 19th Texas Infantry (grave#2637) and Sgt. Charles B. Brantley of the 12th Arkansas Sharpshooters (grave#2673) were accidentally buried in section B.

There are approximately 5,000 Confederate dead (1,600 from the Vicksburg campaign) that were buried in the Vicksburg City Cemetery, known as the Cedar Hill Cemetery, one of the oldest and largest cemeteries in the U.s. that is still in use. They were given plots in a section called Soldier's Rest. J.Q. Arnold, a local undertaker, was contracted by the Confederate government to bury the rebel dead, and kept meticulous records, assigning each soldier a grave number, which was referenced on a detailed map. His lists and map disappeared after the siege, but a portion of the list was rediscovered in the 1960s, detailing the name, rank, company, unit, and date of birth for 1,600 of the interred. The remaining 3,500 soldiers buried there are unknown.

There are approximately 5,000 Confederate dead (1,600 from the Vicksburg campaign) that were buried in the Vicksburg City Cemetery, known as the Cedar Hill Cemetery, one of the oldest and largest cemeteries in the U.s. that is still in use. They were given plots in a section called Soldier's Rest. J.Q. Arnold, a local undertaker, was contracted by the Confederate government to bury the rebel dead, and kept meticulous records, assigning each soldier a grave number, which was referenced on a detailed map. His lists and map disappeared after the siege, but a portion of the list was rediscovered in the 1960s, detailing the name, rank, company, unit, and date of birth for 1,600 of the interred. The remaining 3,500 soldiers buried there are unknown.Near the back of the cemetery, a gazebo on the indian mound provides a great overview of the cemetery and the Yazoo River.

As in many national cemeteries, plaques are placed along the road featuring excerpts from the poem Bivouac of the Dead by Theodore O'Hara, which was originally in honor of the Kentucky soldiers who died in the Mexican War of 1847:

The muffled drum's sad roll has beat

The soldier's last tattoo;

No more on Life's parade shall meet

That brave and fallen few.

On fame's eternal camping ground

Their silent tents to spread,

And glory guards, with solemn round

The bivouac of the dead.

No rumor of the foe's advance

Now swells upon the wind;

Nor troubled thought at midnight haunts

Of loved ones left behind;

No vision of the morrow's strife

The warrior's dreams alarms;

No braying horn or screaming fife

At dawn shall call to arms.

Their shriveled swords are red with rust,

Their plumed heads are bowed,

Their haughty banner, trailed in dust,

Is now their martial shroud.

And plenteous funeral tears have washed

The red stains from each brow,

And the proud forms, by battle gashed

Are free from anguish now.

The neighing troop, the flashing blade,

The bugle's stirring blast,

The charge, the dreadful cannonade,

The din and shout, are past;

Nor war's wild note, nor glory's peal

Shall thrill with fierce delight

Those breasts that nevermore may feel

The rapture of the fight.

Like the fierce Northern hurricane

That sweeps the great plateau,

Flushed with triumph, yet to gain,

Come down the serried foe,

Who heard the thunder of the fray

Break o'er the field beneath,

Knew the watchword of the day

Was "Victory or death!"

Long had the doubtful conflict raged

O'er all that stricken plain,

For never fiercer fight had waged

The vengeful blood of Spain;

And still the storm of battle blew,

Still swelled the glory tide;

Not long, our stout old Chieftain knew,

Such odds his strength could bide.

Twas in that hour his stern command

Called to a martyr's grave

The flower of his beloved land,

The nation's flag to save.

By rivers of their father's gore

His first-born laurels grew,

And well he deemed the sons would pour

Their lives for glory too.

For many a mother's breath has swept

O'er Angostura's plain --

And long the pitying sky has wept

Above its moldered slain.

The raven's scream, or eagle's flight,

Or shepherd's pensive lay,

Alone awakes each sullen height

That frowned o'er that dread fray.

Sons of the Dark and Bloody Ground

Ye must not slumber there,

Where stranger steps and tongues resound

Along the heedless air.

Your own proud land's heroic soil

Shall be your fitter grave;

She claims from war his richest spoil --

The ashes of her brave.

Thus 'neath their parent turf they rest,

Far from the gory field,

Borne to a Spartan mother's breast

On many a bloody shield;

The sunshine of their native sky

Smiles sadly on them here,

And kindred eyes and hearts watch by

The heroes sepulcher.

Rest on embalmed and sainted dead!

Dear as the blood ye gave;

No impious footstep here shall tread

The herbage of your grave;

Nor shall your glory be forgot

While Fame her record keeps,

For honor points the hallowed spot

Where valor proudly sleeps.

Yon marble minstrel's voiceless stone

In deathless song shall tell,

When many a vanquished ago has flown,

The story how ye fell;

Nor wreck, nor change, nor winter's blight,

Nor time's remorseless doom,

Can dim one ray of glory's light

That gilds your deathless tomb.

Tour Stop 9

Fort Hill marks the extreme left edge of the Confederate defense. Situated high on a bluff above the bend in the river north of the city, it provided one of the most defensible locations on the battlefield. It was estimated to be so secure that in the initial assaults on May 19 and 22, the Union Army didn't even attempt to take it. It is such a natural defensive stronghold that when this site was transferred from the Chocktaw Indians to the Spanish under the Natchez Treaty in 1791, they established it as a fort named Fort Nogales, in reference to its black walnut trees. Militaries from France, Spain, England, the U.S., and the C.S.A. have all made use of Fort Hill's natural defensibility.

At the time of the Civil War, the water that could be seen from here was the Mississippi River, but now it is an inlet of the Yazoo. The first battle of the Vicksburg campaign occurred in December of 1862, when Grant ordered Gen. Sherman to attack Chickasaw Bayou north of Vicksburg. The attack was repelled, so Grant moved his forces to the Louisiana side of the river, where they spent the winter. Though this gave his troops a respite from active fighting, it didn't give them a respite from activity. Grant decided to attempt what would have been an incredible feat of wartime engineering had it worked - he dug a canal in attempt to redirect the Mississippi River, which would have allowed Union ships to bypass the Confederate artillery. It proved unsuccessful, though after the war, the river did change course on it's own. Still, Grant credited this digging for keeping his soldiers physically fit for the spring offensive.

When the winter flood waters receded from the Mississippi, Grant marched for a month along muddy roads to a landing southwest of Vicksburg called Hard Times. Here, he was ferried across the river to Mississippi, where he was successful in the battle of Port Gibson, Raymond, seized the capital city of Jackson, and was victorious at Champion Hill and Big Black River Bridge. When he reached Vicksburg, he had marched and fought over 200 miles in less than 3 weeks, forcing the Confederate forces into Vicksburg, where they hoped they would receive reinforcements from General Joseph Johnston. Johnston, who had conceded Jackson, would never come.

Confederate Avenue is the ridge that General Pemberton fortified to defend the city of Vicksburg. Along Confederate Avenue, the blue markers that indicate Union movements give way to the red ones that provide details of the Confederate troops. Maj. Generals Martin L. Smith, John S. Bowen, John H. Forney, and Carter L. Stevenson commanded the Confederate defensive line.

I drove through Vicksburg twice - the first day I arrived late, and by the time I reached the Confederate line, the light of day was fading. On the second day, a storm rolled in as I reached Fort Hill. As a result, both times I was hurried through the last few tour stops, which feature the same locations that were seen from the Union side, but from the rebel perspective.

The Tennessee State Memorial, a 13'10" by 3'2" unpolished granite slab cut in the shape of the state of Tennessee was dedicated on June 29, 1996. Placed by the United Daughters of the Confederacy, it honors the soldiers from that state that served in the defense of Vicksburg.

After Fort Hill, the next official stop is at Stockade Redan, but it's worth pausing at the 26th Louisiana Stockade on the left.

Grant had orchestrated 13 major approaches with the rifle and the shovel, during the siege digging 60,000 feet of trenches in addition to establishing an additional 89 artillery positions with 220 guns emplaced.

Tour Stop 10

Opposing Union General Sherman, C.S.A. General Martin Smith commanded the defense at the Stockade Redan. It is so named because in order to fortify the position, Smith had his men construct a stockade of poplar logs across the Graveyard Road.

As with all the other major defenses, during the initial attacks, the Confederates manning the Stockade Redan were able to repulse the advances of the Union. The rebel success was not without a cost. C.S.A. Brig. Gen. Martin E. Green was warned by his soldiers about the accuracy of Union sharpshooters. Moments after declaring "A bullet has not been moulded that will kill me," he was struck and killed.

The Arkansas State Memorial was dedicated on August 2, 1954. Built at a cost of $50,000 by the McNeel Company of Marietta, GA of Mount Airy, N.C. marble, it is inscribed "To the Arkansas Confederate Soldiers and Sailors, a part of a nation divided by the sword and reunited at the altar of faith."

Continuing across a bridge on Confederate Avenue, the Surrender Interview Site, an unofficial tour stop, is at a short detour to the left on Pemberton Avenue. On July 3, 1863, at 3 o'clock in the afternoon, General John C. Pemberton met with General Ulysses S. Grant to discuss terms of surrender. They were unable to reach an agreement on that day, but exchanged letters during the night, and were able to reach acceptable terms, resulting in the surrender on July 4.

Continuing across a bridge on Confederate Avenue, the Surrender Interview Site, an unofficial tour stop, is at a short detour to the left on Pemberton Avenue. On July 3, 1863, at 3 o'clock in the afternoon, General John C. Pemberton met with General Ulysses S. Grant to discuss terms of surrender. They were unable to reach an agreement on that day, but exchanged letters during the night, and were able to reach acceptable terms, resulting in the surrender on July 4.The original surrender site monument, which was initially slated to be a gravesite marker, was one of the first monuments erected on any Civil War battlefield. Unfortunately, due to vandals and memento seekers, it only stood here from 1864-1867, when it was transferred to the National Cemetery, and later put in storage for it's preservation. It is now displayed in the visitor center. A 42-pounder cannon replaced the original marker, and stood here until 1940, when it was removed for restoration. It was returned to it's position in 1990.

Pemberton was a native of Pennsylvania, and there were many southerners, including other generals, who doubted his devotion to their cause. After the fall of Vicksburg, there wasn't a command available for a 3 star general, so Pemberton resigned his post then served as a lieutenant colonel in the artillery for the duration of the war, leaving no shadow of doubt as to his allegiance to the Confederates.

Incidentally, Maj. Gen. John C. Pemberton's nephew, Col. John S. Pemberton, was a pharmacist that was injured during the war. Like many other wounded veterans, he became addicted to morphine. In his search to find a cure for his addiction, he invented an alcoholic tonic that he would later develop into Coca-Cola.

Tour Stop 11

General John H. Forney commanded the area including the Great Redoubt. Returning to the main drive, near the junction of Confederate Avenue and Pemberton Avenue is the Great Redoubt with the Louisiana State Memorial mounted atop it, which were first seen from tour stop 1, 600 yards across the clearing.

General John H. Forney commanded the area including the Great Redoubt. Returning to the main drive, near the junction of Confederate Avenue and Pemberton Avenue is the Great Redoubt with the Louisiana State Memorial mounted atop it, which were first seen from tour stop 1, 600 yards across the clearing. During my first drive around the park, when I reached the final loop of the park, which comprises stops 11-15, night had fully overtaken the park, so I was unable to take all the pictures I would have liked to take of all of it's features, but I was able to see many of them, and they are well worth exploring. Unfortunately, on my subsequent trip, this loop was closed due to work that was being done for the restoration project.

During my first drive around the park, when I reached the final loop of the park, which comprises stops 11-15, night had fully overtaken the park, so I was unable to take all the pictures I would have liked to take of all of it's features, but I was able to see many of them, and they are well worth exploring. Unfortunately, on my subsequent trip, this loop was closed due to work that was being done for the restoration project.  The Mississippi State Memorial honors the 4,600 Mississippians who served during the siege. The memorial, which was dedicated on November 13, 1909, stands 76 feet high and features a bronze pedestal that was fabricated in Rome.